From Matter to Matter

13th August - 17th September 2019

Barnard Gallery, Cape Town

From Matter to Matter

2019

Ashraf Jamal

Seated in Katherine Spindler’s studio, listening to her as she lays out works in oil, water soluble graphite, and charcoal, one word emerged like a reckoning – sensibility. A favourite in the Eighteenth century lexicon, and in literature most famously examined in Jane Austen’s novel, Sense and Sensibility, the word implies a particular ‘disposition’ or state of mind and heart electrified by passion.

‘The ability of being able to appreciate and respond to complex emotional and aesthetic influences’, sensibility is a quality that compels one to break apart the surfaces of things, the implacability of truth, the better to arrive upon that which matters most but for which we possess no name. It is a quality triggered best at the limit of experience. For Henry James it is ‘a kind of huge spider-web of the finest silken threads suspended in the chamber of consciousness’ that catches ‘every airborne particle in its tissue’.

Something to this effect springs to mind as I gaze upon Spindler’s works. For it is this intuitive sense which drives her. She speaks of ‘something being there’, then asks, ‘but where is there?’ Inspired by the Bill Viola show at the Royal Academy which she saw in February this year, she speaks of ‘searching for the image that is not the image’. This is because for Spindler, as it is for Viola, the image is more shroud than perceptible thing – a penumbral dream, a lure, taste or quality of a thing rather than the thing itself.

Stephen Hawkings is another inspiration, because what intrigues Spindler is not the assumption that black holes exist, but their ‘luminous, entropic, chaotic’ quality. Nothing, for the artist, is ever wholly circumscribed, not even the anti-theological presumption of some primal chaos. Rather, what intrigues her is life’s febrile shifts and twists – its ineluctability. If she speaks of ‘never wanting to commit’, it is not because she is a sceptic, but because there is always ‘this and that, that and this’ – a compound of improbable probables.

The title of Spindler’s latest show, From Matter to Matter, suggests both a condition and a state, a noun and a verb. It is this indeterminacy which is her draw-card, for what her audience is moved by is her ability to conjure empowering feelings or intuitions or dreaded yearnings. Her art, after Henry James, comprises a fretwork of threads, without beginning or end, which, when caught in the ‘chamber of consciousness’, or across the electrical field of a viewers’ body, speaks to our innermost selves.

‘The ability of being able to appreciate and respond to complex emotional and aesthetic influences’, sensibility is a quality that compels one to break apart the surfaces of things, the implacability of truth, the better to arrive upon that which matters most but for which we possess no name. It is a quality triggered best at the limit of experience. For Henry James it is ‘a kind of huge spider-web of the finest silken threads suspended in the chamber of consciousness’ that catches ‘every airborne particle in its tissue’.

Something to this effect springs to mind as I gaze upon Spindler’s works. For it is this intuitive sense which drives her. She speaks of ‘something being there’, then asks, ‘but where is there?’ Inspired by the Bill Viola show at the Royal Academy which she saw in February this year, she speaks of ‘searching for the image that is not the image’. This is because for Spindler, as it is for Viola, the image is more shroud than perceptible thing – a penumbral dream, a lure, taste or quality of a thing rather than the thing itself.

Stephen Hawkings is another inspiration, because what intrigues Spindler is not the assumption that black holes exist, but their ‘luminous, entropic, chaotic’ quality. Nothing, for the artist, is ever wholly circumscribed, not even the anti-theological presumption of some primal chaos. Rather, what intrigues her is life’s febrile shifts and twists – its ineluctability. If she speaks of ‘never wanting to commit’, it is not because she is a sceptic, but because there is always ‘this and that, that and this’ – a compound of improbable probables.

The title of Spindler’s latest show, From Matter to Matter, suggests both a condition and a state, a noun and a verb. It is this indeterminacy which is her draw-card, for what her audience is moved by is her ability to conjure empowering feelings or intuitions or dreaded yearnings. Her art, after Henry James, comprises a fretwork of threads, without beginning or end, which, when caught in the ‘chamber of consciousness’, or across the electrical field of a viewers’ body, speaks to our innermost selves.

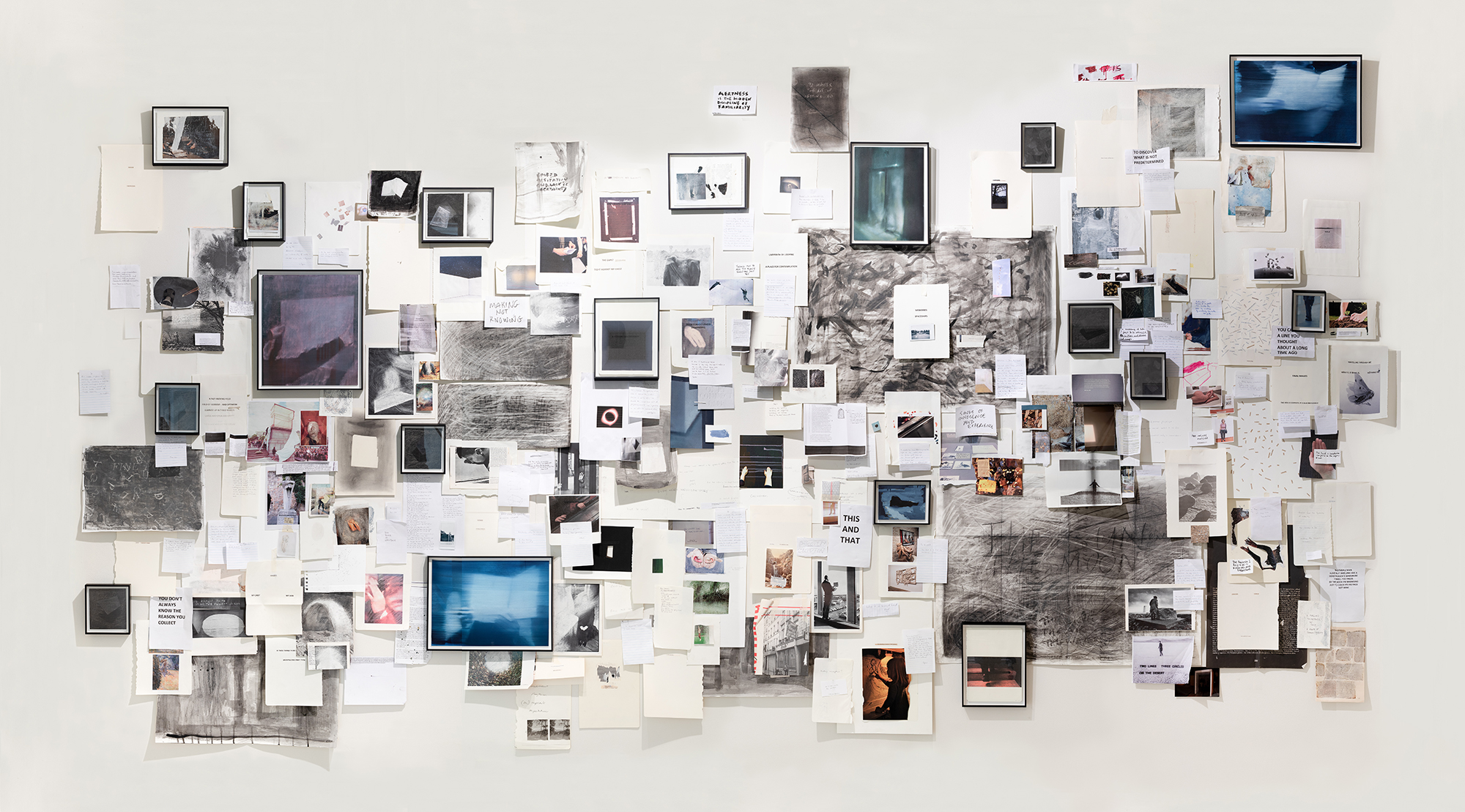

For years Spindler was baffled by Yoko Ono’s seemingly throwaway line – ‘paintings as poems, poems as paintings’ – until, one day, it ‘clicked’. Nothing ever is what it is supposed to be. Everything loops, folds, connects – then blurs. Spindler’s ‘found texts’, cut up, rephrased and recontextualised, are instances of this looping and morphing of meanings and instincts. That no word exists alone does not only mean that it needs another, and another, to produce its fullest force. Rather, what Spindler acutely realises it that all words, all things, inhabit a void, and that meaning, or the feelings we attach to meanings, cannot ever ignore this vacuum.

Hence the artist’s preoccupation with what Alastair Whitton calls ‘the spaces between breaths’, hence Spindler’s preoccupation with ‘complexity and fluidity’, with ‘letting life unfold … in fragments’. After all, ‘how endless is the end?’ she asks. And why should we not ‘discover what is not determined?’

Indeed. In an overly and unduly prescriptive and absolutist era, all the more do we need artists who would embrace the unknown. The very tools Spindler uses, white bread and paper towels – amongst other more conventional appliances – suggests someone who is never wholly enamoured by the dignity of art-making. Rather, what matters far more is the marvellous perplexity it affords. Her jugs of paint brushes are ‘neglected and badly cared for’, she says, the humour belying the fact that what matters most, irrespective of the method and medium used to achieve it, is the grail of some ineffable matter.

As I work my way through the works presented, it is the reverberating mystery that remains. A chair hovers in a near yet oblique distance … hands touch with a feeling I can barely recall … a drooping figure lingers hesitantly between worlds … words, words, words, cling haplessly to surfaces that quiver … nothing binds, and yet everything just does, as Spindler’s world comes into view – as ‘a slow exposure’.

Hence the artist’s preoccupation with what Alastair Whitton calls ‘the spaces between breaths’, hence Spindler’s preoccupation with ‘complexity and fluidity’, with ‘letting life unfold … in fragments’. After all, ‘how endless is the end?’ she asks. And why should we not ‘discover what is not determined?’

Indeed. In an overly and unduly prescriptive and absolutist era, all the more do we need artists who would embrace the unknown. The very tools Spindler uses, white bread and paper towels – amongst other more conventional appliances – suggests someone who is never wholly enamoured by the dignity of art-making. Rather, what matters far more is the marvellous perplexity it affords. Her jugs of paint brushes are ‘neglected and badly cared for’, she says, the humour belying the fact that what matters most, irrespective of the method and medium used to achieve it, is the grail of some ineffable matter.

As I work my way through the works presented, it is the reverberating mystery that remains. A chair hovers in a near yet oblique distance … hands touch with a feeling I can barely recall … a drooping figure lingers hesitantly between worlds … words, words, words, cling haplessly to surfaces that quiver … nothing binds, and yet everything just does, as Spindler’s world comes into view – as ‘a slow exposure’.

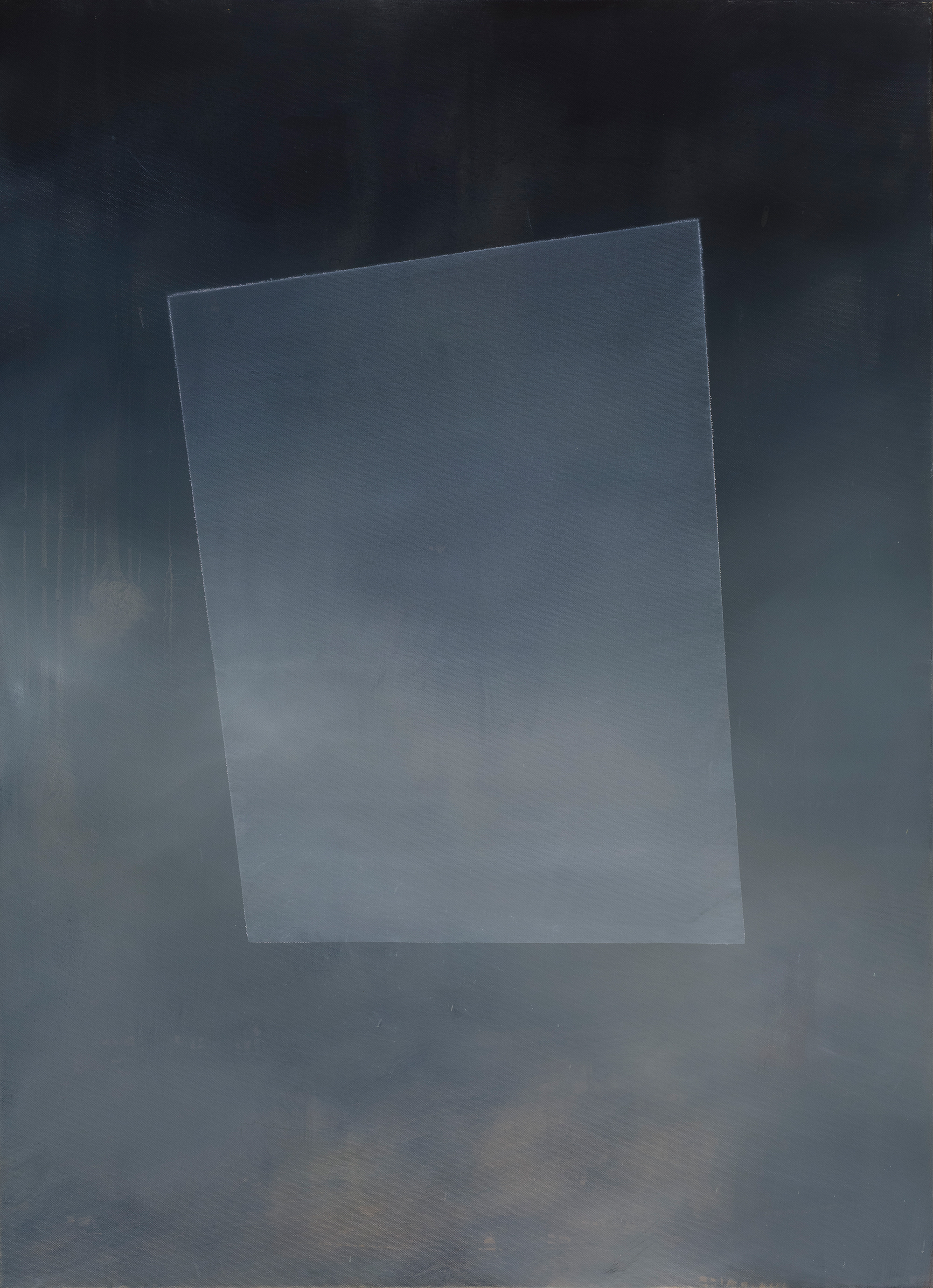

Reconfiguring

2019

oil on canvas

190 x 160 cm